Over the course of her career, Susana Carmona, a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist at the Gregorio Marañón Institute of Health Research, has used brain imaging to study the distinctive brain activity patterns in many different conditions: psychosis, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder. But in 2008, she decided to switch her focus to a new condition, and after her first brain imaging experiments, she was shocked.1 “I had never seen changes that were so profound and so marked,” she said.

The condition in question? Pregnancy.

Carrying and birthing a baby changes the brain and body in ways that extend long beyond childbirth. One of the more well known, but less understood, consequences of these changes that has long existed at the margins of both medicine and society is postpartum depression (PPD). Often written off as the “baby blues,” this form of depression that occurs after giving birth is much more insidious. It affects one in eight new mothers, but is still underdiagnosed, undertreated, and underdiscussed.

Lauren Osborne hopes that a future PPD blood test can measure changes in levels of neurosteroids that precede PPD.

Will Kirk

There is a stigma associated with mental illness, said Lauren Osborne, an OB/GYN at Weill Cornell Medicine, and that is especially true for PPD. The stigma is partially fueled by insufficient understanding of the biological underpinnings of these diseases. “The lack of biological markers impairs the way the public and physicians view our illnesses,” she said.

Carmona, Osborne, and other researchers are working to fix this. They are searching for molecular signatures that can be used to predict who might be at risk for PPD, what biological processes are going haywire, and how to treat it. In recent months, their work has yielded a flurry of newly identified signs of PPD everywhere from the brain to the blood. Each new finding is one more piece of the complex puzzle.

“[Each study] incrementally advances our understanding of the biology,” Osborne said. “We just have to figure out how to connect all these little pieces together.”

A Blood Test for PPD

As an OB/GYN, Osborne knows firsthand just how inadequate current PPD screening can be. “We do a really, really bad job of identifying and treating people with postpartum depression,” she said.

Physicians administer surveys to assess current depression symptoms on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale or the Patient Health Questionnaire, or they may ask about the patient’s or their family’s history of depression. However, all of these strategies capture a current snapshot of the patient’s mental health, which doesn’t allow doctors to predict a patient’s risk of PPD, said Jennifer Payne, a psychiatrist at the University of Virginia.

Payne has discovered epigenetic predictors of PPD, which she hopes can help distinguish people with PPD from those with other forms of depression.

Jennifer Payne

As a result, diagnoses and treatments are easy to miss. One study reported that as few as three percent of people with PPD are properly diagnosed and fully treated. “We wouldn’t accept that for pretty much any other kind of illness,” Osborne said.

However, PPD also offers a unique opportunity. Unlike other forms of depression, PPD is explicitly triggered by a biological phenomenon—pregnancy. That could make it easier to find markers of PPD by following individuals before, during, and after pregnancy and childbirth, and measuring what is different between people who ended up developing PPD and those who did not.

For example, physicians have long known that hormones flood a person’s body during pregnancy to trigger the bodily changes required to carry and deliver a baby. Progesterone is one such critical hormone that thickens the lining of the uterus to enable successful early embryonic development. It continues to support a healthy pregnancy by preventing further ovulation and premature uterine contractions.

However, hormones have also been implicated as potential culprits in PPD. Researchers previously hypothesized that PPD is triggered in some people by sudden drops in hormone levels.2 Another theory is that PPD is the consequence of metabolic byproducts of these hormones interacting with the nervous system. Progesterone, for example, can be broken down and converted into neuroactive steroids, which are molecules that can bind to receptors on neurons. Some of these molecules, such as allopregnanolone, can have a positive effect on key signaling pathways while others can have the opposite effect.

In a study published earlier this year, Osborne and Payne teamed up to test whether these neuroactive steroids are correlated with PPD.3 They recruited over 100 pregnant women who did not have a history of depression and measured these molecules in their blood during the second and third trimester. After the women gave birth, the researchers continued to collect data and found that a subset developed PPD. The women who ended up developing PPD were more likely to have higher third-trimester progesterone levels than other pregnant women. They also had higher ratios of certain neuroactive steroids (such as isoallopregnanolone compared to pregnanolone) which are known to negatively affect signaling pathways and lower ratios of others with protective effects.

“It seems that the balance of the ratio of the positives to the negatives is off in those women who go on to develop postpartum depression,” Osborne said. Osborne doesn’t yet know exactly why these patterns appear, but she suspects that the pathway that breaks down progesterone into neuroactive products might be getting stuck at early stages, leaving women with higher levels of certain molecules. She expects that these molecules might suppress inflammation to different degrees, something her other studies have shown is correlated with PPD.

“Eventually we may get to a point where we really understand the mechanism and that can help us to develop new treatments,” she said. “But even if we don’t fully understand the mechanism that they represent, they can still be useful.”

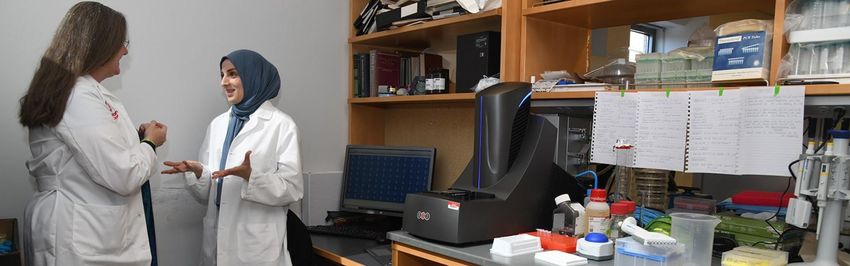

The Osborne lab studies the brain and immune system during and after pregnancy.

Weill Cornell Medicine

In particular, she is interested in developing a blood test that measures the levels of these neurosteroids to estimate a person’s risk of PPD. This would allow physicians to refer a high-risk patient to additional resources to provide more support during and after childbirth, when they might otherwise be vulnerable to PPD.

Payne, a close collaborator of Osborne’s, already has some experience developing PPD tests. More than a decade ago, Payne began investigating whether hormone-level changes could be triggering PPD by causing molecular changes to the DNA—not mutations, but rather, epigenetic changes. DNA is coated with small molecules such as methyl groups that mediate the conformation and accessibility of genetic information. These molecules attach to and detach from DNA in response to environmental factors, including hormone levels.

Through animal studies, Payne found that estrogen-based hormones had a particularly strong effect on DNA methylation of two genes: a histone-binding gene (HP1BP3) and another gene (TTC9B) that had previously been linked to depression.4 Using blood collected from women before childbirth, she discovered that differences in the methylation of these genes actually predicted whether women would develop PPD.

“To my knowledge, this is the first real replicating blood marker that is predictive of a future mental illness,” Payne said. She and her team have already started developing blood tests based on their epigenetic biomarkers in partnership with Dionysus Health. The company is currently conducting studies to predict women’s PPD risk during pregnancy and then following them through the postpartum period to assess whether the prediction was accurate. Payne expects that in approximately two years, they will have enough data to support an application for Investigational Drug Exemption from the FDA. “Then we can start to study [the test] in real-world use,” Payne said.

Birth Transforms the Brain

Thousands of miles away in Spain, Carmona read about Payne’s epigenetic studies of PPD; she was amazed. “Everybody is trying to understand the phenomenon through different routes,” she said. “We just have three or four different pieces of the puzzle, but the puzzle still needs to be completed.”

The piece that most fascinates her is the brain itself. Carmona’s group uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to study the anatomy of the brain over time. Certain regions can get bigger or smaller, and they can use the scans to measure this change in volume.

In a recent study, her team scanned the brains of 88 women during pregnancy and postpartum.5 They focused on the hippocampus and amygdala because of their role in emotional regulation and memory—two important factors in PPD. As in Osborne’s study, they didn’t know which of the women would develop PPD, but they surveyed the participants’ depression symptoms throughout the study.

Researchers in the Osborne lab identified neurosteroids whose relative levels during the third trimester of pregnancy predicted PPD.

Weill Cornell Medicine

They found that women who had more depression symptoms tended to have increases in the size of their right amygdala. But for Carmona, the more interesting result lies in the way that birth experience changed the brain. In addition to a depression survey, her team surveyed the women on how positive or negative their experience with childbirth was. Women who had worse birth experiences had larger increases in the size of their hippocampus, a result that surprised Carmona because it was consistent across both hemispheres of the brain.

The idea to study birth experience came not only from the scientific literature, but from a community of mothers that shares their experiences with Carmona’s research team via the Instagram channel @neuro.maternal. They emphasized that their emotional experience during childbirth was hugely impactful, perhaps even more so than the physical experience. “Childbirth is such an intense experience, so we want to know what might make it empowering or traumatizing,” Carmona said.

Osborne, who was not involved in this study, was interested in the potential for brain imaging to link PPD biomarkers back to the brain. “If something that we’re measuring outside the brain is connected to postpartum depression, it must be because there are effects happening in the brain,” she said. But she noted that it is hard to interpret the functional consequences of changes in the size of brain regions.

MRI scans are hard to do in pregnant people—as Carmona knows firsthand—and the kinds of scans required to measure brain activity, such as positron emission tomography, use radiation that doctors avoid administering to pregnant people. Carmona is currently using the longitudinal data her team has collected to train an AI-based algorithm to predict which brain changes might increase PPD susceptibility, which could minimize the number of scans that would be required for future diagnostic testing.

Ultimately, she hopes her results also highlight the interventions that are within reach. The mothers in the NeuroMaternal group reported that the support they felt during childbirth made the experience much more positive. “Birth experience is something that can be manipulated,” she said. “Paying attention to how you treat a woman during this intense time is a very cheap and easy intervention, and it can make a difference.”

Biology to Overcome PPD Stigma

Even though a predictive test for PPD may still be some years away, Payne hopes the work from her and other researchers can still spark a mindset shift. “My hope is that it changes the standard of care from reactivity to prevention,” she said.

Currently, however, there are still societal barriers to accelerating this work. With rumors that grants about women’s health are getting flagged at US government agencies, financial support for this work is increasingly limited. The National Institutes of Health initially planned to terminate funding for the Women’s Health Initiative, a large-scale study of breast cancer, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and more in understudied postmenopausal women; however, this decision was recently rescinded. This reflects an ongoing trend in biomedical research, Carmona said. “There is sex bias in biomedicine,” she said.

Nonetheless, there are signs that the medical field’s view on PPD may be shifting. In 2023, the FDA approved the first-ever oral drug to treat PPD. The drug, zuranolone, is a synthetic version of allopregnanolone, a neuroactive steroid that Payne and Osborne have studied.

While this drug seems to be effective for treating PPD, there are still many more unanswered questions about the disease’s causes and mechanisms. “Sometimes we live in a paradigm in which a molecule in a brain region seems to be important, but we don’t know what is the cause and what is the effect,” Carmona said. “We’re right at the beginning of trying to understand the neurobiological basis of postpartum depression.”

She believes that tying her brain imaging work with the neuroactive steroid research from Payne and Osborne could help answer those questions. But she also highlights the importance of years of epidemiological and psychological research on the social and environmental factors that promote PPD.

To Payne, biomarkers may add a new layer to our understanding of what is—and what isn’t—PPD. She has long suspected that PPD might be biologically distinct from other types of depression that can also occur during the postpartum period but aren’t driven by hormone levels. She is currently studying the neuroactive steroid pathways in women with depression symptoms after childbirth, some of whom have the epigenetic biomarkers of PPD and others who don’t. She expects that those who don’t have the epigenetic biomarkers might just have standard depression, while those with the biomarkers may have more dysregulated neuroactive steroid levels.

This kind of biological subphenotyping can reveal heterogeneity in mental illnesses that could lead to better treatments, she said. She also hopes it can legitimize the experience of women who are suffering from PPD.

“I hope that having a blood test for mental illness will decrease stigma, particularly around postpartum depression, because it will be clear that there’s a biological basis for this and that it’s not just about pulling up your socks and getting on with the business of being a mother,” she said.

Source link